I’ve attended Scala.io, the French Scala conference. This year, after the previous editions were based in Paris, the conference relocated to Lyon.

Martin Odersky, the Scala creator, was the keynote speaker on the first day. In his talk he shared his insights on the road ahead for the language (and, to some extend, for its ecosystem). Scala 2.12 will be the first release to target exclusevely Java 8 as its runtime, for this reason Scala 2.11 will still be around for a while (at some point this year Scala 2.11.9 will also released). He talked about the issues in making use of the new Java 8 bytecode features (default methods and lambdas, to name two) made the compilation process in some case even slower (up to 10-20% slower). This made the Scala compiler team backtrack and stick with the current compiler approach to patch objects to make traits and functions work. Ultimately, the new Scala version will arrive with more than 30 new features.

Scala 2.12 is not out yet, but the planning for the next major release has already begun (working name 2.13 at this point). Similar to what Intel is doing with its processors evolution, Scala is adopting a tick/tock release process: every two iterations one is dedicated to the compiler, the second is dedicated to platform enhancements. As 2.12 will be focused on compiler modification to make use of the new Java 8 features, 2.13 will continue the improvement work on the standard library. A lot of discussion is still going on, but the general idea is to split the standard library in two parts: Scala core and Scala platform. In this layout, everything needed by the scala compiler and broadly used by almost every Scala programmer will make into the core module. Everything else will end up in the platform component, with the goal to have at some point a Scala environment with “batteries included”.

Even with all this work on Java 8 VM, it’s now a reality the fact Scala is not only targeting the JVM. Scala.js is getting quite mature and it has almost reached the point when it could be considered production ready. Also Scala native (to run Scala on LLVM) is making a steady progress. The development is not going as fast as Scala.js due to all the low level C code still needed (with the I/O library one of the most relevant example).

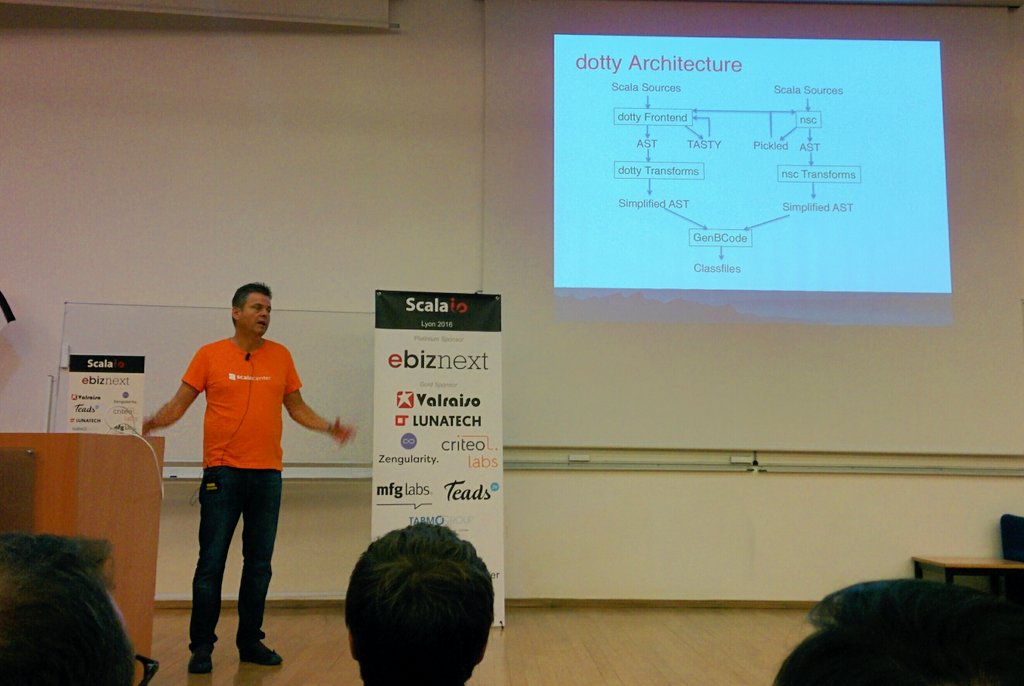

The real stars of the keynote were DOT and Dotty. DOT is a minimal language deeply based on dependent types (where types can depend on values) used to prove the type soundness of the Scala programming language. After 8 years, the proof is completed and now exists a model, proved sound, to have a better reasoning on the next steps in the language evolution. Along with DOT, also Dotty (what it will eventually became the new-new scala compile) is near a first public release: a MVP is expected at some point during the next year. Martin highlighted critical points in the effort, with the infamous null and uninitialized variable be the two hard to tackle. At this moment, Dotty has two-thirds of the lines of code of the current compiler (50K loc vs 75), and it was written as functional as possible where immutability was one the capstone. With some imperative trickery under the hood and heavy use of caching (thanks to the immutability) Dotty is currently outperforming the current compiler with a two times speed up (and improvements are still possible).

In his vision, the future of Scala, even if pending more on the functional side, the essential elements of the programming language should include:

- functions (pure, mathematical functions)

- classes/objects

- strict evaluation (but Scala collections need a better implementation for lazy-evaluated views)

- local type inference (global one would be great, but this is conflicting with some of the scala feature)

- implicits (a very powerful, but frequently misused, feature).

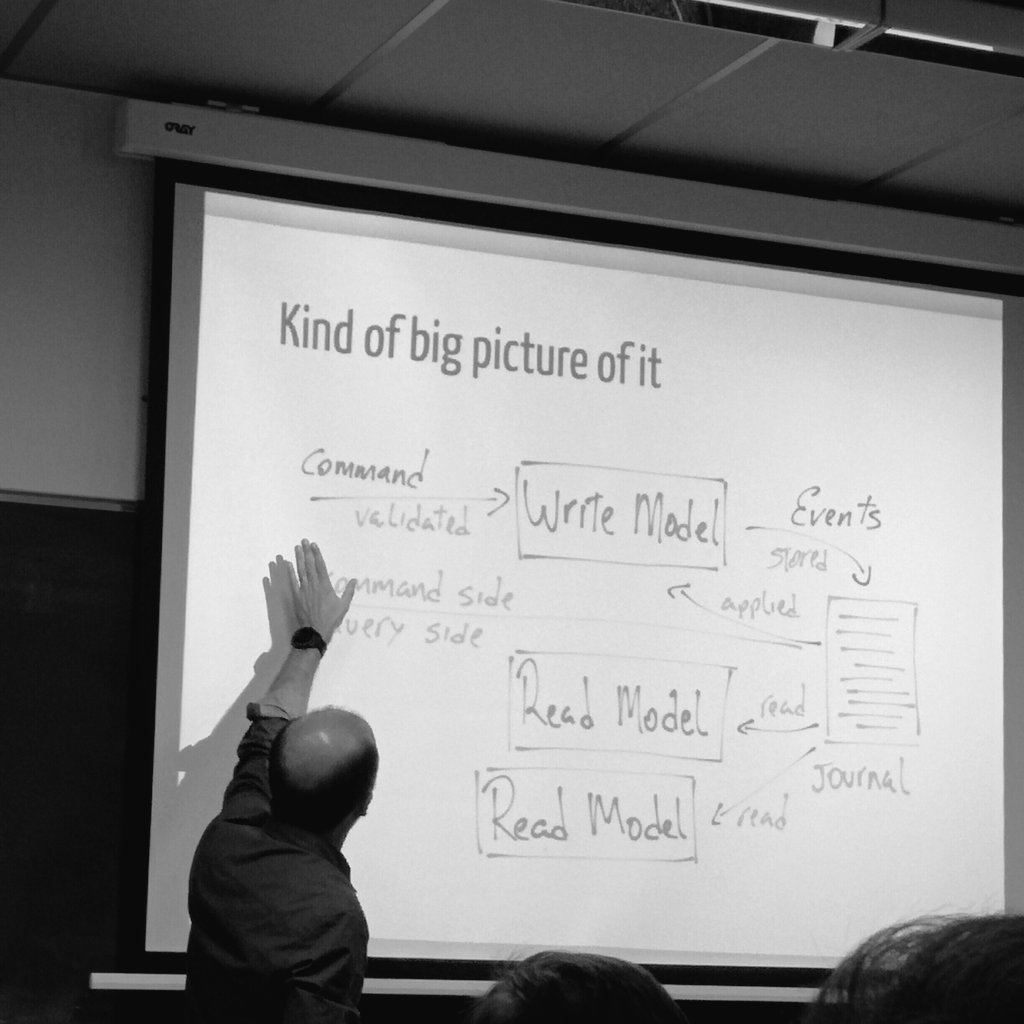

I spent the morning of the first day in Renato Cavalcanti’s workshop on CQRS/Event Sourcing with Scala. The scope of the workshop was to build a small example of an orders management system using a framework called Fun.CQRS. In CQRS we have basically two complementary models: the command/write model and the the query/read model. On the write side we receive commands and emit events, while on the read side we consume events to generate views. In general one command can produce one or more events, this depends on the particular command/context.

Usually CQRS is complemented with Event Sourcing, where we store all the events that occurred on the system in an event log. This log becomes then the source of truth for the application. The true power of CQRS is actually coming from the use of the Event Sourcing.

We also briefly touched one of the main concepts of the Domain Driven Design: aggregates. Aggregates are defining a context bound and maps almost directly to the Command model. It also introduces a name for a main application concept. When implemented it can includes one or more objects, that at any given point in time they have to be kept consistent. This is true for a given aggregate instance, we are not constrained to keep more aggregates consistent with each other.

In general, we apply commands to aggregates, moreover we also keep the history of past events inside the aggregate. At this level we can have logic to decide whether we can accept a given command, or if we have to rejected it. While we have this freedom on the commands management, once an event is stored, it happened and we can’t do anything about it. One of the rule of event source is to never change the past. In the functional programming world, we can think of the current aggregate state as a foldLeft of all the past events.

As it is natural thinking of Akka actors as aggregate, they are the basic backend implementation provided by Fun.CQRS. In Akka, an actor receive a message (a command), and it processes messages one at the time. With the Akka persistence plugin all the messages can be persisted in an event log. Fun.CQRS tries to give an higher abstraction for this kind of pattern. Ultimately we define a behavior for Aggregates in terms of protocol (commands and events) and actions (command and event handlers).

To conclude we saw the Read model, implemented via so called Projections. They generate views out of persisted events, and they are represented in Fun.CQRS as function with this signature

Event => Future[Unit]

Projections are functions that don’t produce any meaningful value, but they have the purpose to just consume events. The Future bit is present to model the asyncronicity of the data loading processing that almost always involves I/O.

After lunch, in his talk Micheal Cohen, a tech recruiter from New York spoke about the perception of the Scala community from the “decision makers” in some of the biggest tech company. The talk was really fun and it left me this great quote:

When something dies in Scala, it dies in an awesome way.

After a quick introduction on Shapeless, (I lost the first part due to the room change) the rest of the first day was dedicated to functional programming design patterns with two different views on data validation.

Daniela Sfregola dedicated her talk to an approach for beginners, starting from what we already have in the standard library (Option/Either), and then moved to Cats showing examples with Xor and Validated. Her conclusion was to pick an error representation and stay consistent with it, use types and make them easy to use.

On the other hand, Markus Hauck showed two design patterns: Monoid and errors management. In his introduction he made the parallel between Lego/Duplo vs FP/OOP. In his view with OO we have large specialized blocks, with a limited freedom in their use, while FP provides small composable building blocks. He then show two examples: Monoid and Errors management.

Monoids are from category theory, and intuitively have the purpose to combine “stuff”. He shows a couple of examples, and a more practical application inside Spark (the famous “work count” example). When he switched to errors management, his starting point was the OO solution to the problem: exceptions. Checked exceptions are bad and ultimately Scala didn’t implement them. The idea to have errors management enforce at compile time was the right intuition though, so in Scala we made errors first class value (like Either/Try). Moreover, try/catch blocks don’t compose very well.

This solution has still shortcoming, the most relevant is this kind of error management is still fail-fast (it stops at the first exception). He then showed an example of Validate. We also have Ior for warning when we don’t treat validation error as terminating errors.

During the second day we had two keynote speakers in Bill Venners and Jamie Allen. In his talk, Bill Venners discussed his idea on the hard relationship between software developers and users. In case of successful applications, users make hard to change anything. We bother with this struggle because the ultimate goal is to produce better software.

In his opinion, this approach to move the things forward and to always produce better software is hardwired in the Scala community culture. He then showed a couple of use cases of ScalaTest who made users complaint on Twitter. The conclusion was that ultimately we want that something potentially not correct in our program should not even compile.

The evolution of software is often painful to find the right amount of changes the user base would tolerate, and this put even more burden on the software maintainers to reduce the pain for the users to follow this evolution over time. Users behavior is something we have to take in consideration when we design new functionalities (and eventually remove old stuff). In his mind, the benefit of change must always greater than its cost.

Another pain point are the silent killers, features that silently behaves differently in new releases. This almost always break code in surprising ways. To ease the migration path, we should help users with migration tools.

Jamie Allen took a detour on the more business oriented side of Open Source development. Nowadays the missing ingredient is the tight integration between the open source community and the enterprise. It’s hard to find a middle ground that allows FOSS to grow organically in face of the formal process implemented by big corporations. On the hand, in the past when FOSS projects received a strong input from the enterprise world, the community felt left out. In Jamie’s opinion the ScalaCenter is an effort in right direction to preserve Scala future.

I then attended the talk about typesafe dependency injection for reactive applications, where Grzegorz Wilaszk presented his library to make easier to express asyncronous dependencies for Akka projects. With some type level programming (and an heavy dose of Shapeless) he presented a reasonable and scalable solution to the problem.

After this session, I’ve attended a light session where Marconi Lanna presented beautiful Scala one liner.

Before lunch, Miles Sabin presented the TypeLevel project. He defined Typelevel as a community devoted to “pure, typeful functional programming” that takes inspiration from other functional languages without trying to reimplement haskell in Scala. Back in the 2014, in order to solve the problems in the compiler that makes harder this typeful kind of programming, TypeLevel announced a fork of the compiler. The project, for various reasons, stalled during the 2015. The project restarted and first version is available, I think they take the right approach making the TypeLevel compiler an “early access” version rather than a completely diverging one.

TypeLevel has still an agenda full of possible improvements (and bug fixing) on the compiler, this list includes: multiple implicit blocks, partial types application, compile time improvement for inductive implicits. In the future steps, the approach would be to make the minimal disruption, easing the transition from one compiler to the other (and back).

I completed my two days at Scala.io with the workshop on typeclasses. Typeclasses are a pattern implemented originally by Haskell in order to have ad-hoc polymorphism, a completely different approach than the more traditional one, using inheritance. With Julien Truffaut in the role of instructor/guide we had the chance to write our own version of SemiGroup, Monoid and Function typeclasses.